Religious Bigotry in Nigerian Society towards Yoruba Traditions and Spirituality: An Overview

In 1842, Christian missionaries made their initial presence in what is now recognised as Badagry, Lagos, Nigeria. The arrival of missionaries and the subsequent colonisation of Nigeria, as we understand it today, marked a series of events that would alter the course of history for many. The Western influence during this period was marked by the transatlantic slave trade, a period that witnessed millions of Africans sold into slavery, displacing them across the world. Western imposition in Africa introduced a cascade of cultural transformations, and most significantly, the systematic eradication of African cultural identity. The transatlantic slave trade and the religious and cultural changes brought about by colonisation have left an enduring legacy, one that demands reflection and understanding.

Today, Nigeria stands out as one of the most religious countries in the world. Characterised by the presence of mega churches and affluent pastors featured on the Forbes list. Religious leaders in Nigeria have not only ascended spiritual heights but have also reached the peaks of wealth, ranking among some of the wealthiest individuals on the African continent. A significant portion of the Northern region is also predominantly governed under sharia law. The third constitution of Nigeria, adopted in 1979, declares the nation a secular state, preventing any government from adopting an official state religion. This constitution also reinforces the right to freedom of religion and prohibits discrimination on religious grounds. Currently, Nigeria is reported to have a population of 51.1% Christian, 46.9% Muslim, and 2% practicing traditional or other faiths.

Yet, it's crucial to note that within the country's strong religious landscape exists a significant issue of religious bigotry. This prevailing intolerance poses an ongoing threat to preserving traditional belief systems and cultural practices, that predated the widespread influence of Christianity and Islam, amongst the various ethnic groups and tribes within Nigeria. This article will largely focus on Yorùbá spirituality.

Before the arrival of Christianity and Islam, the Yorùbá people, were largely immersed in a rich and intricate belief system known as Ìṣẹ̀ṣe. This complex system encompasses a diverse array of spiritual practices and observances deeply ingrained in the fabric of Yorùbá identity and culture. The displacement of Yorùbá people through slave trade allowed these practices to also spread to Cuba, South America and the United States. Central to Ìṣẹ̀ṣe is the acknowledgment of Oludumare as the supreme being and creator, surrounded by numerous Orisha (deities) regarded as intermediaries, reflecting various manifestations of Oludumare. The guide for Isese is known as Ifa. Adherents believe that Ifa hold the words of Oludumare, from which believers seek wisdom and guidance. At the heart of Ìfa lies the belief in goodness and virtue as a guiding principle. For the Yorùbá people, it was a holistic worldview that permeated every aspect of life and death, shaping their values, social interactions, and understanding of the cosmos.

The once revered belief system and practices of the Yorùbá people, however, are no longer held in high regard. Instead, they are confronted by widespread demonisation across Africa and the diaspora. Negative superstitions and misconceptions have cast a disparaging light on traditional practices, branding them as demonic and regressive. Simultaneously, some followers of Christianity and Islam often take turns proclaiming the superiority of their faiths, claiming that their religious convictions are the exclusive path to salvation while deeming traditional practices as evil. This constructs a narrative that characterises traditional spirituality as satanic, perpetuating its bastardisation even post colonialism

Examining the narratives disseminated by the transatlantic slave owners and Western society provides valuable insights into the widespread nature of religious prejudice and the marginalisation of African spirituality today. It highlights the extent to which this stigmatisation is embedded in the collective consciousness of present day African and black communities.

The anti-black rhetoric propagated by the transatlantic slave owners and preachers played a pivotal role in shaping the negative perceptions surrounding African identity. By intentionally depicting African practices as primitive and satanic not only justified the forced conversion of the enslaved to Christianity, but also fostered distrust among fellow blacks, with superstitious fears also fuelling their apprehension towards one another. Writer and white supremacist, Myrta Lockett Avary, wrote “negroes stick together and conceal each other’s defections; this does not proceed altogether from race loyalty; they fear each other; dread covert acts of vengeance and being “conjured.”

In a 1706 essay by Cotton Mather, a slave owner and preacher, titled “The Negro Christianized” he wrote that; “Very many of them…worship Devils, or maintain a magical conversation with Devils: And all of them are more Slaves to Satan than they are to You, until a Faith in the Son of God has made them Free indeed. Will you do nothing to pluck them out of the Jaws of Satan the Devourer?” This portrayal of enslaved Africans as devilish aimed to dehumanise them, erase their native beliefs, and ultimately position Christianity as superior. These narratives also served as a powerful tool in enforcing servitude and promoting white supremacy a legacy that endures to this day.

During this era, it was also common for superstitions to dominate discussions. People frequently turned to superstitious explanations for things they couldn't rationalise, such as deaths and illnesses, often attributing blame to witches and those perceived to engage in what was then considered as conjuring, allowing more hysteria and fear to build up on what had been warped by Western ideology. Paradoxically, whites were fearful of the native practices and knowledge held by the enslaved and there was deep apprehension around being poisoned by them. To address these fears, laws were implemented in Southern America that prohibited the enslaved from exchanging knowledge amongst themselves regarding plants, roots, and herbs. These laws were effectively a means of controlling the spread of ancestral information, thereby disrupting the continuity of the indigenous knowledge that is passed down orally through generations.

The marginalisation and distortion of African spirituality continues to create a barrier for indigenous belief systems and practices to exist in society without repugnant discrimination and stigma. Appreciating the historical context may cultivate a more inclusive and respectful discourse on African spirituality in the present day.

Herbalism and spirituality amongst the Yorùbás

In the context of Yorùbá culture, the knowledge of ewé àti egbò (leaves and herbs) has always been an instrumental piece of knowledge, even though it also faces stigma today. In the present day, modern medicine has understandably taken precedence, although it does still coexist with traditional approaches to healthcare. The knowledge of herbs and leaves are an important part of health and life for the Yoruba people. Yoruba herbalists would use various herbs to make medicine for their communities and would have a vast knowledge of natural substances and what cures what aliment. It is not unusual to observe spiritual divination, within herbalism. Yorùbá herbalists (Onisegun) may also incorporate ọfọ̀ (incantations) to extend beyond purely medicinal purposes to tap into the spiritual. Within the Yoruba’s lies a discreet sect known as the Awo’s, which sits at the core of Yoruba spiritual thought and practice. Knowledge of their practices is shrouded in secrecy, requiring initiation into the Awo’s, as the knowledge for type of divination can only be passed to initiates.

Fast forward to more recent times, there has been little to no change in the narrative surrounding traditional culture and spirituality. The surge in intense religiousness in Nigeria and the prevalence of Afrophobic themes in African popular culture, particularly in the Nollywood industry, has effectively fuelled and sustained the hysteria and demonisation associated with African spirituality.

Nollywood

Nollywood is one of Nigeria’s biggest industries, releasing about 2500 films a year making it the second largest film industry in the world. Nollywood continues to be a cornerstone of Nigerian’s popular culture, providing entertainment and influence for those across Africa and the diaspora. Popular movie tropes that are commonly explored in Nollywood movies are, family, marriage, poverty and the supernatural. The latter being the most polarising of them all.

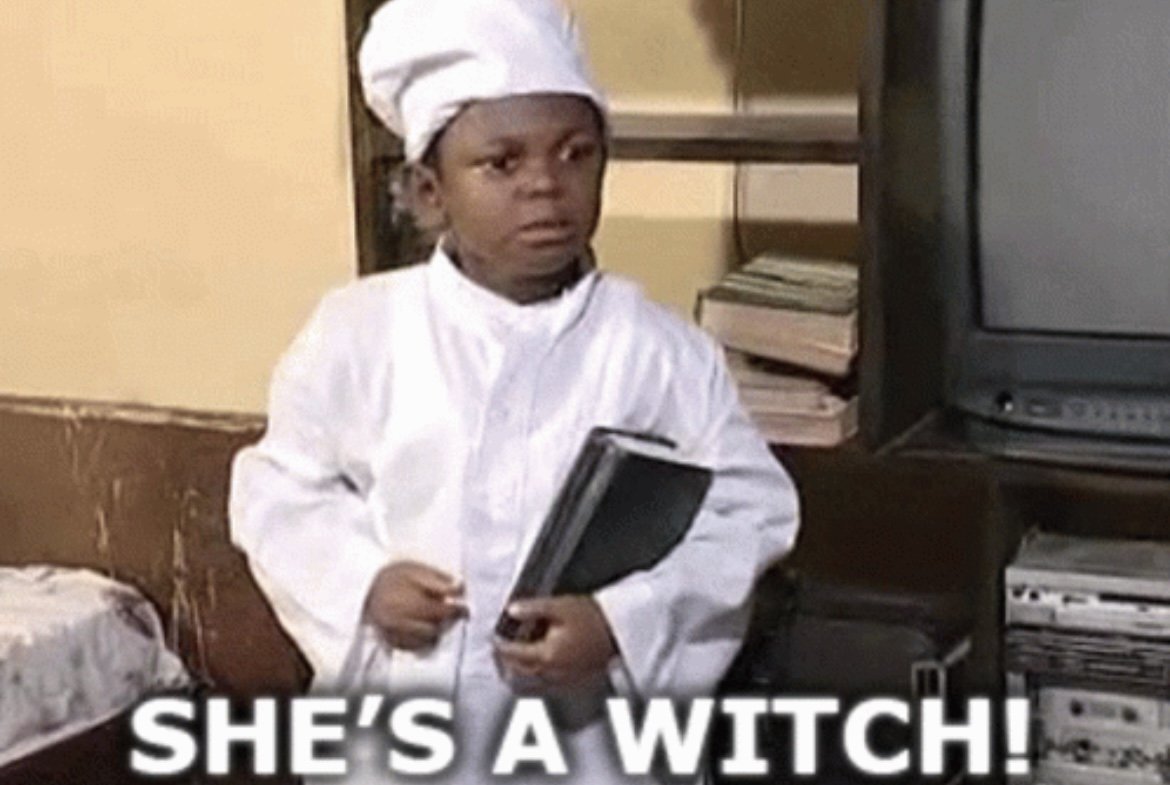

The Nollywood industry places an exaggerated emphasis on supernatural themes, frequently portraying a struggle between forces of good and evil. In the Nigerian context, this manifests as a battle between popular religion and traditionalists, with traditionalism often being associated with cultism, witchcraft, revenge, and death. The typical storyline often features a protagonist aligned with a popular religion, such as Christianity, who emerges as the hero, neutralising satanic entities in order to save the day. While this narrative and theme have proven popular and marketable in the Nollywood industry as they strongly resonates with African audiences, it would be disingenuous to state that exposure to these films hasn't contributed significantly to cultural distortion and miseducation. These movies consistently perpetuate the superstitions surrounding supernatural forces that are believed to be acting against ordinary individuals; which creates an atmosphere of fear and superstition within African culture, particularly towards situations that are beyond people's control and cannot be easily rationalised, as well as anything that deviates from religious beliefs.

The persistent association of traditionalism with negative forces such as cultism, rituals, and sacrifice, reinforces the misconception that these elements constitute the true essence of traditional spirituality, thereby branding those who continue to practice it as evil and backward.

In the academic Journal of Religion & Film, Floribert Patrick C. Endong stated, "Many religion-oriented movies born from the Nigerian motion pictures industry (code-named Nollywood) are kinds of religious propaganda. They aim not only at moralizing but also at persuading audiences to embrace specific models of spirituality." Endong later stated, "In such films, Christian values and symbols are generally portrayed as superior to those of other religions as well as the unique and most appropriate solution to any political, economic, and socio-cultural problem that may exist in Nigeria."

Ultimately, this covert manifestation of religious propaganda has played a role in fostering cultural erosion and attitudes of religious bigotry within Nigerian society. The far reaching impact of these films extends well beyond simple entertainment; they have moulded negative perceptions of traditionalism and culture, with their influence unconfined to Africa but also permeating through to the diaspora, even among the younger generations.

Present day demonisation: Rema concert

In November 2023, Nigerian singer Rema, held a sold out concert at the O2 Arena in London. Rema's visual elements, however, received mixed reviews from fans. He appeared onstage wearing a red mask and rode a stationary horse. Rema also incorporated an artificial bat into his performance. This use of this stagecraft, coupled with dark and provocative aesthetics, drew strong responses from some concert attendees and online fans, with some individuals expressing concerns about satanism in Rema's imagery. Following the uproar, Rema took the time to explain the meaning behind his imagery, stating that the artificial horse featured in his performance was a reproduction of a Benin artifact. He further explained that the mask he wore was a replica of the renowned Queen Idia mask, with the Bats being symbolic of the Edo night sky.

What becomes apparent from the negative reactions to Rema's concert is the complex dynamics people have with things that don’t align with their religious beliefs and anything that goes beyond their current level of comprehension. The reactions brought to light the tendency in African society to hastily label unfamiliar things as satanic, propagating religious bigotry that is rooted in a lack of understanding. The discussion surrounding Rema's artistic choices not only raises questions about the intersection of art and cultural expression, but also reveals the widespread impact of how religious bigotry has penetrated African communities, essentially making it a cultural staple.

Conclusion

Religion possesses the ability to shape our worldview and influence our thought processes. However greater care needs to be taken to prevent the dissemination of narratives fuelled by bigotry that often threatens to erode cultural heritage. Religious intolerance can only function to marginalise and miseducate. To preserve the integrity of the Yoruba and the wider African identity, it is crucial to recognise that, despite differing religious convictions in today’s society, discussions about indigenous practices should involve more thoughtful consideration and cultural awareness.

By letting go of the negative narratives that limit knowledge, we become better equipped to comprehend and respect the practices of our forefathers; thereby facilitating the preservation of our collective heritage. Embracing a more open minded and informed approach also helps to narrow the gap of misunderstanding between different beliefs, contributing to a greater level of cultural understanding within society. This, therefore, provides the chance to gain a better understanding of both our own identity and the identities of those who came before us.